Monstrous Margins

Reimagining Architecture’s Abject In-between Space

Alleys, tunnels, stairwells, elevators, and parking garages…

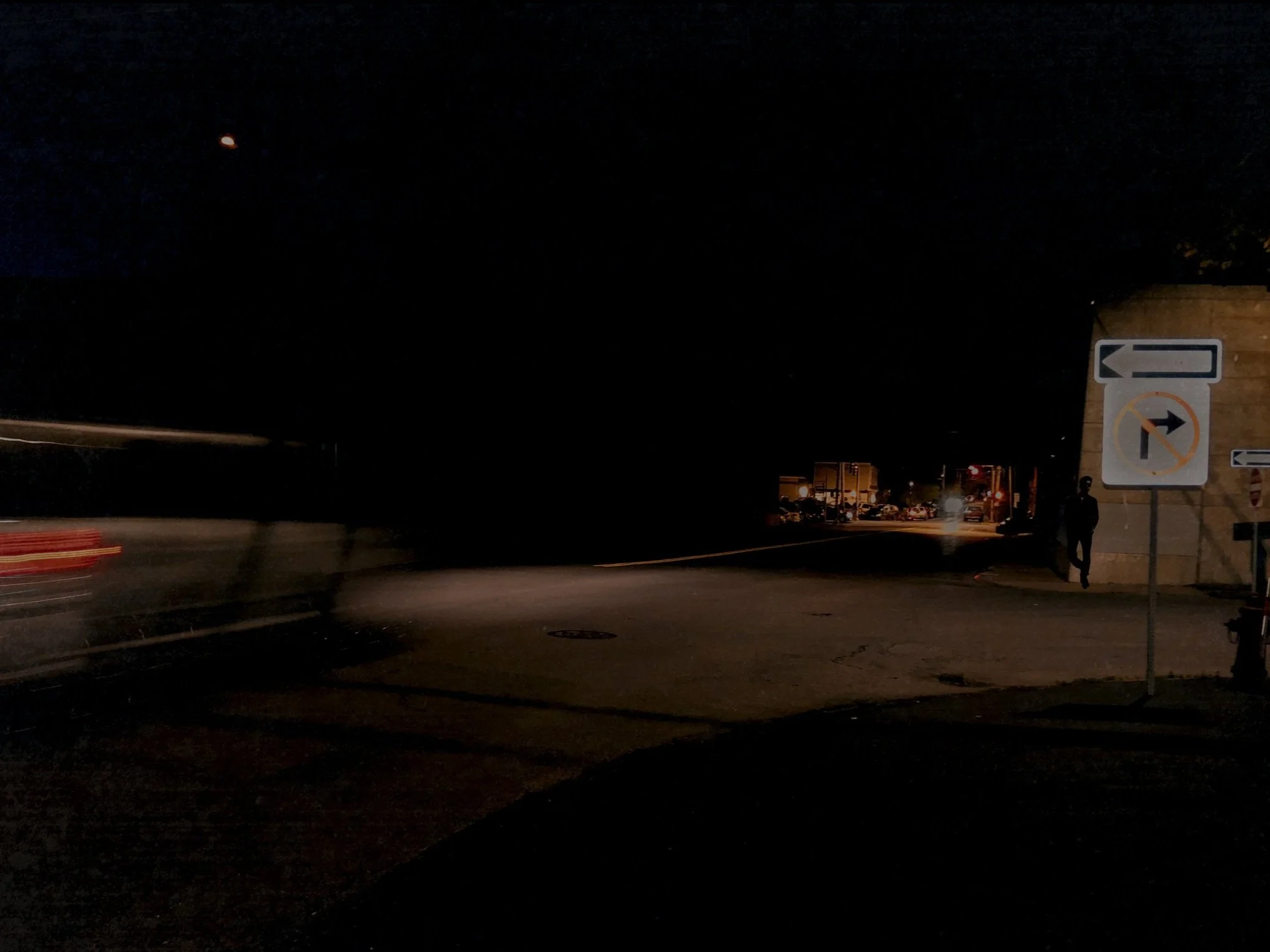

These transitory zones are widely represented as gendered fear-spaces across our pop culture media—from the classic slasher film to the true-crime podcast. They permeate every scale of our built landscape, and while for many they are simply a place of passage, they have been consistently identified by women as harboring potential for violent assault in academic scholarship¹. These spaces exist along the margins of architecture and urban design projects, and it is within these liminal zones that we will focus.

Philosopher Julia Kristeva describes abjection as an emotional response encompassing dread and repulsion one experiences when encountering imagery, objects, or situations that portend possible bodily harm or death². “Abject space” is an architectural phenomenon arising from the synthesis of aesthetic and physical characteristics that, together with sociological factors, compose experiences of abjection that are most often gendered.

On paper these transitory zones appear innocuous, but in situ they frequently contain traits that contribute to perceptions of danger. These traits spark innate sensory responses3, resulting in hypervigilance—a heightened sense of awareness and trepidation. These physical and aesthetic characteristics may include sub-optimal spatial dimensions (e.g., long, narrow, easily blocked, limited visible exits, and concealed niches), poor lighting, material decay, staining, low occupancy, and physical evidence signaling illicit activity.

Hypervigilant navigation through, or avoidance of, these spaces is a clear expression of inequity in the public realm for women, and those who experience misogyny4. Architects may be unable to directly influence social elements of fear, but we can profoundly impact physical and aesthetic experiences of these spaces. This course will serve as a research and design laboratory for testing this hypothesis.

Research: This seminar is structured to reinforce inclusive and collaborative research and design practices. The first portion of the semester focuses on research and analysis. We will identify problematic spaces and engage with local constituencies—through the use of collaborative safety audits⁵ and an open feedback channel—to understand the specific physical and aesthetic elements that trigger fear. We will then dialogue with governing bodies, architects, and urban activists to uncover ongoing initiatives impacting these spaces, and interrogate local policies, building codes, and other potential constraints—with an eye toward reinterpretation. Using this foundational research, we will transition into the design phase.

Design: Students will iteratively experiment with an abject space and propose a radical redesign. Proposals should consider physical and aesthetic characteristics identified in the audit; site ownership and maintenance; impacts of temporal and climatic changes; surveillance systems and other technologies; and of course, potential social, economic, political, and health-related outcomes of their proposal.

The objective is to remove, or at least substantially reduce, elements that trigger perceptions of potential danger. To test the effectiveness of proposed interventions, students will present their proposals at a final review in which community members will be invited to offer critical feedback. Following these reviews, students will participate in a public exhibition of their work.

1. Examples of this scholarship span at least the past four decades. A few key studies are: Valentine, Gill. 1989. “The Geography of Women’s Fear.” Area 21 (4): 385–90; Valentine, Gill. 1990. “Women’s Fear and the Design of Public Space.” Built Environment (1978-) 16 (4): 288–303.; Gardner, Carol Brooks. 1990. “Safe Conduct: Women, Crime, and Self in Public Places.” In Social Problems. 37 (3): 311–28; Koskela, Hille. 1999. “‘Gendered Exclusions’: Women’s Fear of Violence and Changing Relations to Space.” Geografiska Annaler, Human Geography, 81, no.2: 15.

2. Kristeva, Julia. 1982. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. European Perspectives. New York: Columbia University Press.

3. For studies regarding innate human responses to spatial conditions see: McAndrew, Francis. 2019. “The Psychology, Geography, and Architecture of Horror: How Places Creep Us Out.” Academic Studies Press. McAndrew, Francis T., and Sara S. Koehnke. 2016. “On the Nature of Creepiness.” New Ideas in Psychology 43: 10–15.

4. My research thus far focuses broadly on women, though I aim to expand this to be inclusive of any persons who suffer from misogynistic transgressions.

5. The safety audit will follow the guidelines of those designed by Ontario, Canada’s Metropolitan Action Committee on Violence Against Women and Children (METRAC). Details can be located on their website, www.metrac.org

* All images are my own—an alley, stairwell, and highway overpass in Syracuse, NY. 2020.

Confronting the impending passage under the highway overpass

View down the fire stair in Shaffer Hall, Syracuse University, 2019

Bank Alley, Syracuse, NY, 2020